Did you lock the door to your house today?

How about your windows? Are you sure? Maybe that’s not quite correct. You should check again. Oh, they still haven’t changed? But maybe you should check one more time. And—

And that’s anxiety.

Maybe you’re worrying about someone breaking into your house. Maybe you’re worrying about making a social slip-up in front of someone new you’re meeting today. Maybe your heart starts racing as you think about how maybe when you press send on that email, it won’t actually send to the correct person and will instead send to quite literally everyone else in your contacts, including that friend you haven’t talked to in a year and also your third grade teacher. For some reason.

The anxiety could be mild—just a fleeting notion that runs through your mind, then disappears. Or maybe it’s all-consuming, taking up space in your thoughts all throughout your day until you realize you’ve lost hours’ worth of memories after spending them worrying.

Whichever variant you experience, it can be reduced to be more helpful than unnecessarily concerning—especially as the human stress response was designed more to deal with immediate threats (a predator hunting you down) than a long-term “threat” (deadline next week).

What is anxiety, and what really makes it a problem?

Anxiety can often be confused with fear, though there are some clear-cut differences. While fear concerns the present and the belief that something dangerous is happening in the moment, anxiety means worrying about the future. Though this may have been helpful when humans were hiding from or escaping predators, in most situations in everyday life, this is more inconvenient than it is helpful.

Anxiety can cause lashing out, the need to escape, or freezing up, which are often difficult to overcome—survival instincts are controlled by the amygdala, after all.

The limbic system (image source: Wikimedia Commons)

To explain the significance of the amygdala—the amygdala is one of the major structures of the limbic system, which is the brain’s emotional center. Especially during but not limited to the adolescent years, the limbic system has more direct control of decision-making and self-control. These decision-making signals typically pass through the prefrontal cortex (logical brain), which is right behind the forehead relative to the human face, but the amygdala has the power to override the prefrontal cortex—particularly during situations of high emotion or stress.

There are multiple types of stress—for instance, acute, chronic, episodic acute, traumatic, environmental, psychological, and physiological (Physiology, Stress Reaction). Many of them are linked to each other in some way; chronic stress can lead to psychological effects, which can lead to physiological effects, which can overall put strain on the body.

Anxiety can add to stress as well, piling on not just mentally, but physically as well. Not just that, but over time, it can cause symptoms such as:

- difficulty focusing and concentrating

- restlessness

- irritability and frustration

- weakness

- shortness of breath

- rapid heart rate

- nausea

- hot flashes

- dizziness

That is why it is a concern when the National Institute of Mental Health estimates a prevalence between the ages 13 and 18 years of 25.1 percent and a lifetime prevalence of 5.9 percent for severe anxiety disorder.

Amygdala memories & the autonomic nervous system

At times, the amygdala can form its own memories and trigger anxiety or panic attacks based off of the information it retains, even without the active memory’s awareness of it.

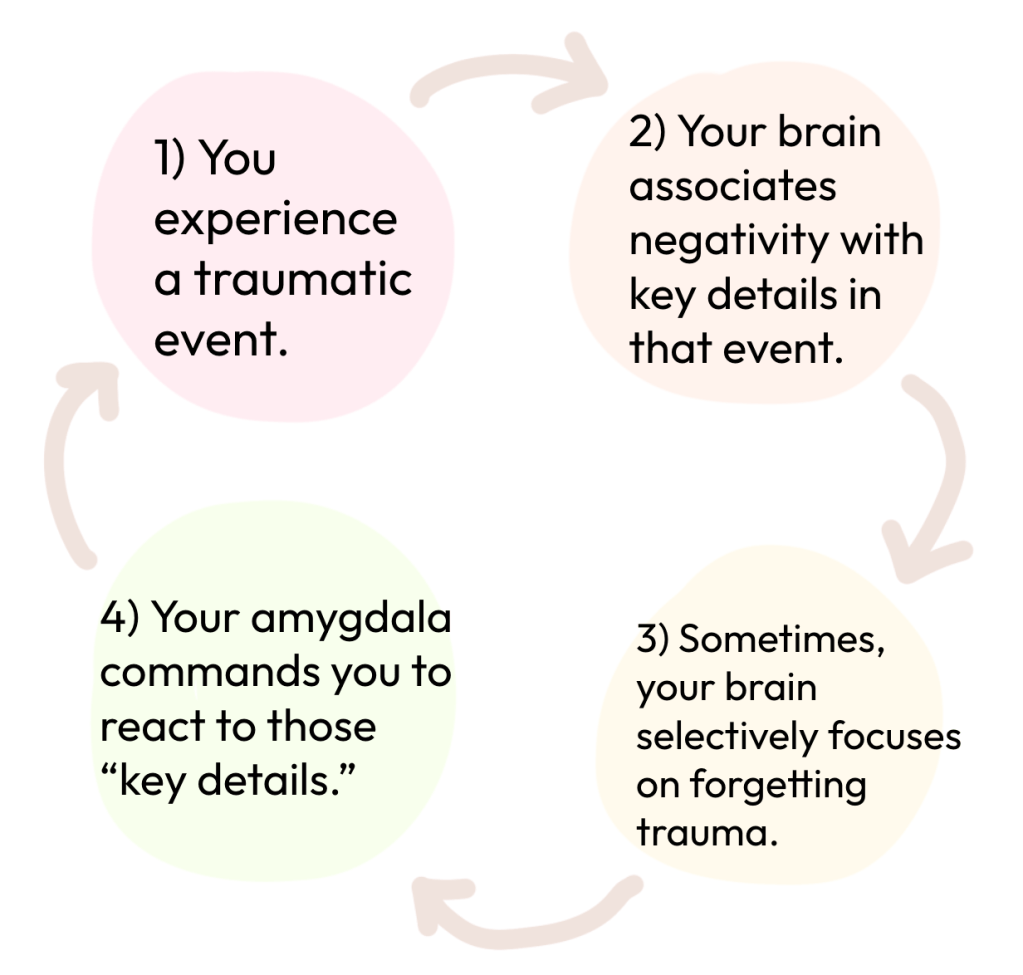

The cycle has four main steps: experiencing a traumatic event, the brain associating negativity with the key details of that event, the brain focusing on forgetting traumatic experiences, and the amygdala reacting when it recognizes those key details later on. Key details could be anything from auditory to olfactory to situational cues—from the smell of a soap to the prickling of watching eyes, the amygdala chooses what to remember and how it thinks it should react when it encounters those details.

Graphic of the amygdala memory cycle (image source: Hanbi Gim)

When the amygdala reacts, it activates parts of the autonomic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system is composed of two smaller nervous systems: the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS, or PSNS). The sympathetic nervous system activates during times of high anxiety and activates the physical symptoms—for instance, quick and shallow breaths. The parasympathetic nervous system calms the body down from that reaction, allowing for rest and energy conservation.

Treatment & techniques

The trick is to rewire the amygdala.

There are several techniques to achieving exactly that, and they often work best when used in collaboration with each other. Some of these techniques are:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy → exposure therapy, which associates good with previously negative memories by gradually increasing positive experiences in response to negative cues

- Certain medications can help you train your brain more effectively

- Studies show that sleep, diet, physical activity, and your gut biome can all affect your mental state. Adjusting lifestyle factors can lower anxiety and panic

- Dopamine baseline adjustment can make events more enjoyable rather than dread-inducing or even boring, as dopamine is the chemical that allows people to enjoy things and want to do them again

These methods combined are the most effective way to take control of anxiety and panic—and many of them don’t need a lot of money or professional help to get started on doing. It’s time to take this as a call for action, whether it be for yourself or someone else.

Resources:

The main book used for information in this post was Rewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and Worry by Catherine M. Pittman and Elizabeth M. Karle.

Any other resources cited in text.

Leave a comment